By Anna Porter, Queen’s Quarterly 121/3 (Fall 2024)

Jack McClelland used to tell the story of how Farley first appeared in his office, a small, red-haired, wild man who wanted, more than anything, to be a writer. He thought words had the power to change the world. I think that is what he was trying to do with People of the Deer, the book that opened the debate about the fate of the peoples of the North, the so-called “barren lands,” which had never been barren and where greed, incompetence, and injustice passed for government policies. As Margaret Atwood wrote in her introduction to High Latitudes, the book “was also an X in the sand: it marked a crucial turning point in general Canadian awareness.”

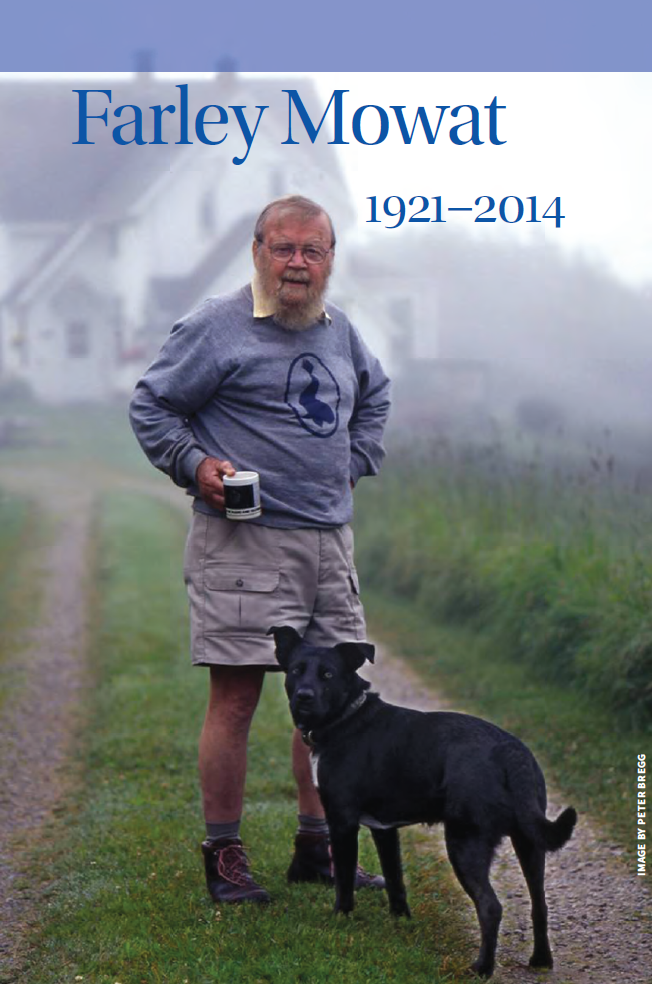

It’s almost impossible to admit that Farley Mowat is dead. It’s even harder to contribute a traditional RIP. Farley was many things to many people, but he was certainly not peaceable. He was cantankerous, argumentative, vehement, passionate, opinionated, bent on changing the world, while there was still time – and, once he concluded we had spoiled our world beyond even his capacious talents to save, he was bent on saving the remaining non-humans. In a letter to Jack McClelland, Farley had promised not “to grow old gracefully. I’m going down the drain snarling all the way.” His nickname in the army was “Squib” – “a small tube of black powder used to ignite a large explosive charge,” was how his father explained the word. Angus Mowat had been the first Mowat to have acquired the moniker and, to avoid confusion, Farley added another “b.”

I have known Farley most of my life. I have read all he has written and, like about ;@ million other people, I am a fan. I was also one of his critical readers and, eventually, his publisher.